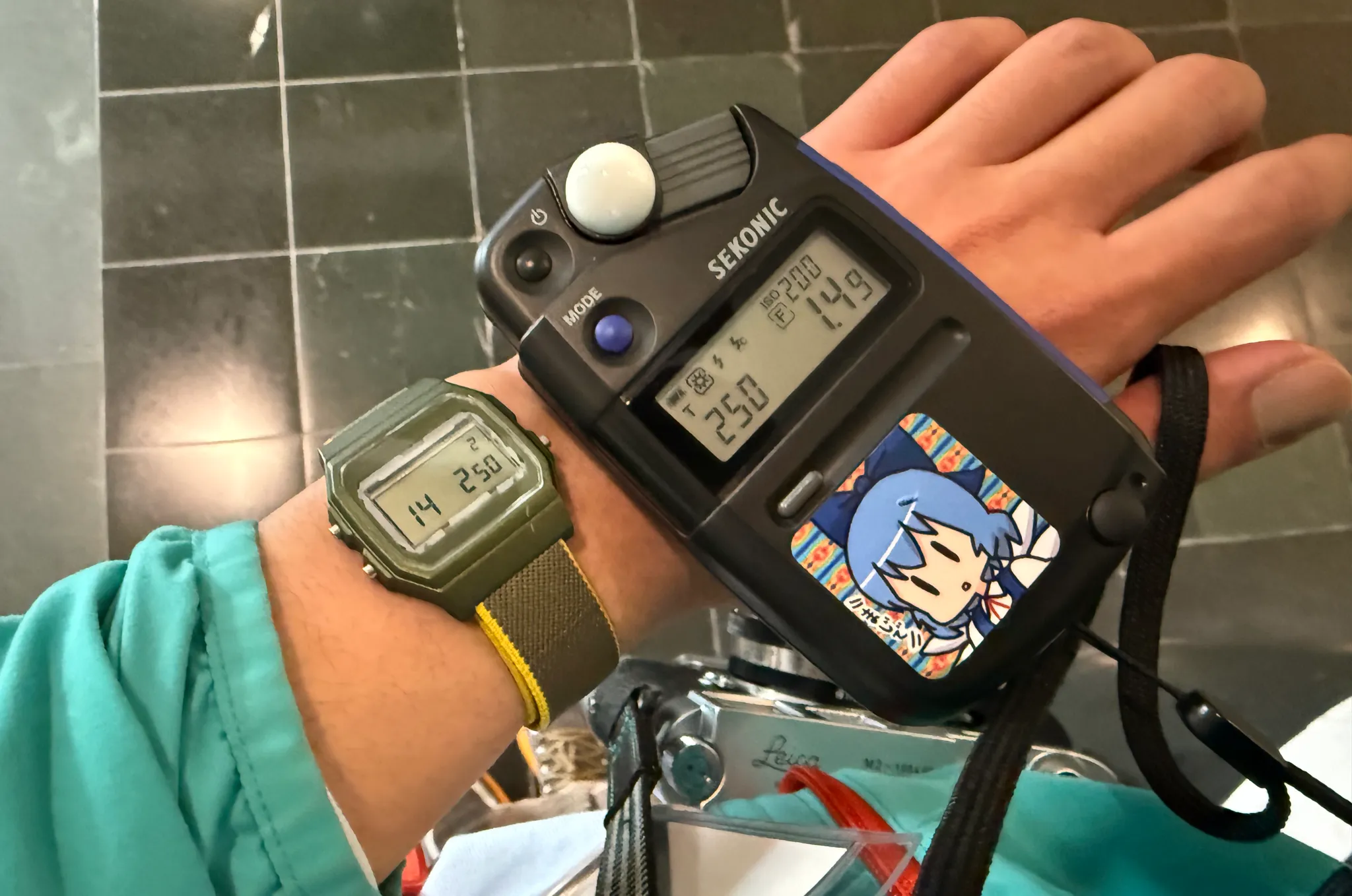

In my spare time, I've been slowly chipping away at the Light Meter Watch. The goal is to build an easy-to-use meter good enough for film photography (and maybe even do a small production run!) I'm building off the Joey Castillo's fantastic work on Sensor Watch, repurposing the venerable Casio F-91W.

When conceptualizing this project, the first hurdle was obvious - where to place the light sensor? Ideally, the sensor should have line-of-sight to the outside world, past the LCD, internal plastic frame, and bezel decals.

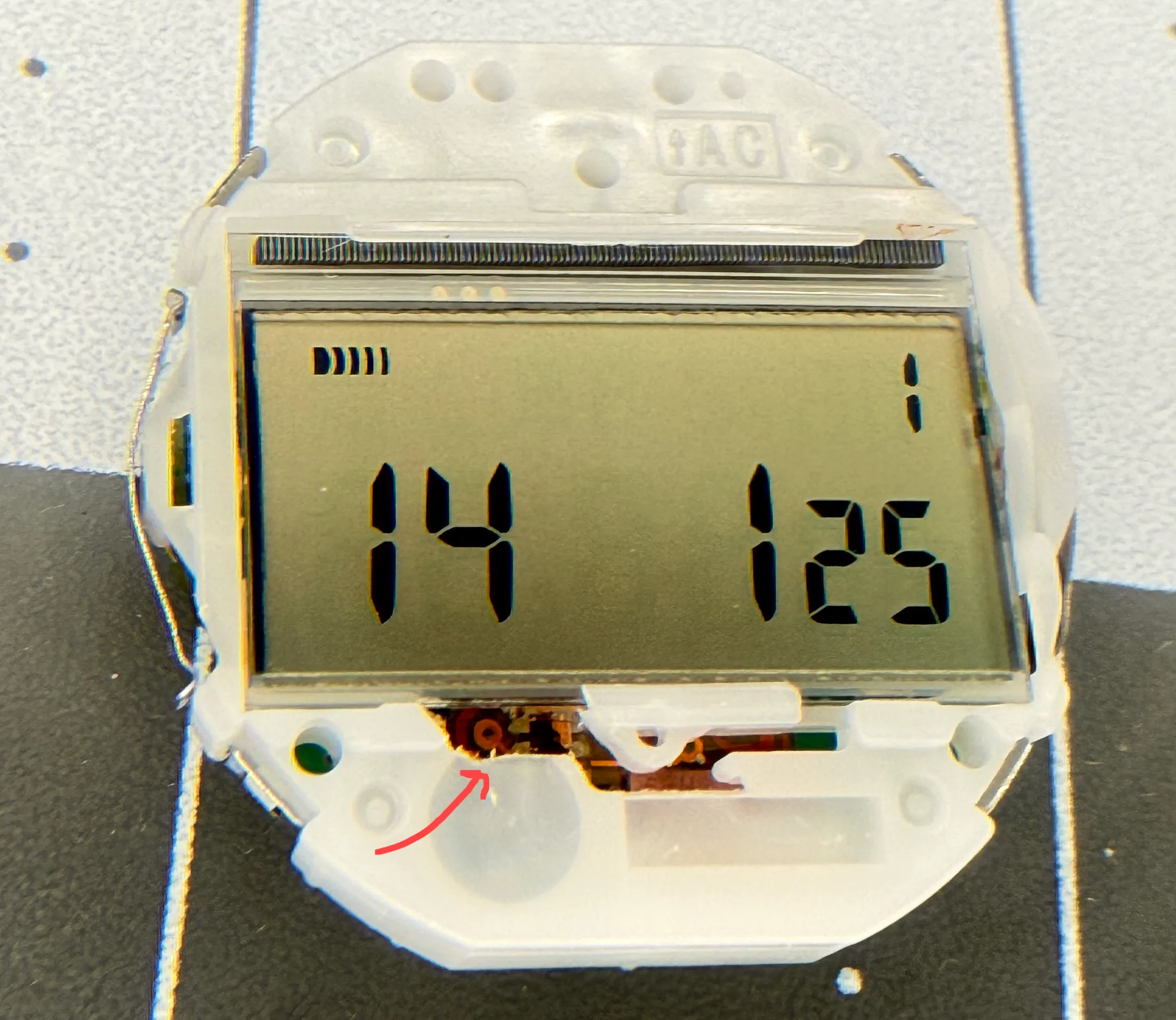

After some squinting (and lots more sketching, measuring, and datasheet searching), I arrived at this sensor flex design, using the AMS TCS3400 color light sensor. The sensor is nestled between some capacitors and the flex connector, placed just low enough to peep through the gaps in the internal Casio module's frame.

The only problem? The bezel decal covers it up, so it has to go!

Research

I'm not the first to have done this - turns out, there's a healthy Casio modding scene, found on forums like r/casiomods. There's also a great article from SHELLZINE.

This post just documents the process that works for me, as well as any additional observations. I really don't want to be burning through a whole bunch of watches when it comes to making a batch of these.

Process

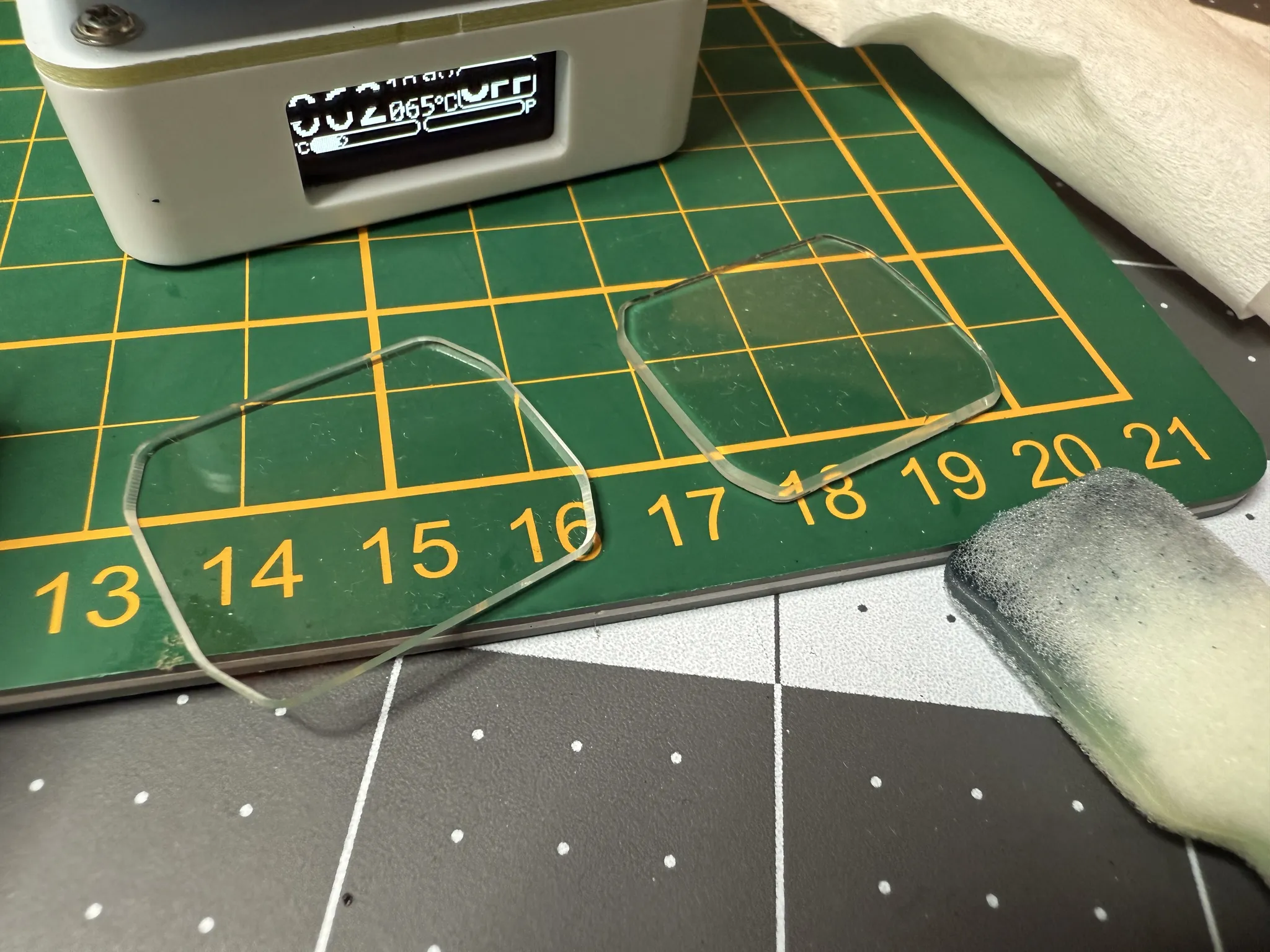

Removing the Crystal

- Preheat watch face-down on hotplate for 1min @ 55C.

- Set SMD rework hot air station to 155C, high air flow, ~1 cm nozzle dia.

- Heat the crystal from the inside of the watch for 1min 20sec. Focus on evenly heating the bezel. You want to heat up the adhesive around the edges of the crystal.

- Using gloves or a towel, grip both straps, one in each hand. Use your thumbs to pop out the crystal. This will take a bit of force; watch out for the crystal flying away!

- Repeat as needed.

Removing the Decal

- Prepare hot plate at ~70C.

- Place crystal on hotplate for a few seconds, decal-side down. Squish the crystal briefly to ensure contact.

- Scrape away decal using swabs and isopropyl alcohol. I recommend foam-tipped plastic cleaning swabs and a plastic scraping tool.

- Repeat as needed.

Warnings and Observations

F-91W vs. A158WA

The A158WA is a variant by Casio that uses the same internal module, and is thus fully compatible with Sensor Watch. The only new features A158WA brings are a chrome finish on the plastic case and a steel watchband.

However, I noticed considerable differences between these two models when it comes to crystal and decal removal.

- Crystal Adhesive

- Both watches use an adhesive to bond the crystal to the case.

- The F-91W uses a glue, primarily applied around the edges of the crystal. After removal, it's not uncommon to find some bit of glue that didn't release, leaving a shard broken off and still attached to the case. While this isn't necessarily an issue, it looks terrible visually, and would be unacceptable in a production run.

- The A158WA uses an adhesive sheet cut to the outline of the bezel. The adhesion feels similar to that of 3M VHB tape. This differs from the F-91W in that the adhesion is more even across the face, but is easier to release cleanly. As I didn't know this prior, I had to do some more heating passes on the A158WA; enough to case some slight warpage on the case. However, once I got the adhesive to release, the whole crystal came out cleanly!

- Scratch Resistance

- The F-91W's acrylic crystal scratches extremely easily when scraping off the decal with a solvent. I used acetone for my first attempt, which was way too strong and resulted in fuming and tons of scratches. Even isopropyl alcohol plus a plastic cleaning swab can cause microscratching if not careful.

- Meanwhile, the A158WA's crystal did not scratch at all, despite also being acrylic (N=1)! The decal is bonded more strongly than the F-91W. I ended up having to use several passes of IPA and even a metal scraping tool. Such harsh treatment would have certainly destroyed an F-91W crystal, but I was pleasantly surprised to see the A158WA crystal survived intact.

tl;dr: consider the A158WA for crystal mods over the F-91W; you will have a better time.

Don't Let Things Get Melty

Last bit of warning: I've found the line between cleanly releasing the crystal and turning the watch into a goopy mess to be fairly slim (with my methods, at least). If you overheat the watch, it will warp. If you overheat the front crystal, it will warp when you push on it. If something smells burnt, you applied too much heat. Be methodical and slowly increase the heat until you figure out a process that works for you.